Lightroom gives you a million and one ways to complete most photo edits. Having options is important. No two photos are alike, so no two edits are alike either. In this article, I’ll show you how to correct skin tones using Lightroom’s color curves.

There are times when the best way to edit color in general, and skin tones in particular, is to use Lightroom’s Color Curves. After reading this tutorial, you’ll be able to; measure RGB skin tone numbers to give you a general idea of which edits your photo needs, and correct the color issues using Lightroom’s Color Curves

Finding the color numbers

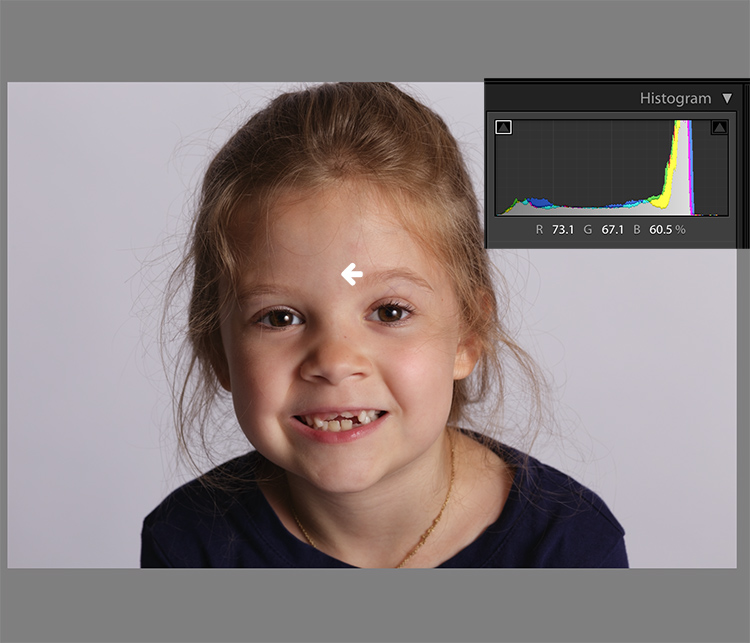

The image below is a photo that came out of the camera with a pretty good white balance and skin tone. Do you see the numbers under the histogram? Those are Red, Green and Blue (RGB) numbers.

You can display the RGB numbers for your photos too. In Lightroom’s Develop module, hover your cursor over the area you want to measure. Look under the histogram for the corresponding RGB measurements.

These measurements tell us that the pixels next to the arrow in the screen shot had the following measurements:

- Red: 73.1%

- Green: 67.1%

- Blue: 60.5%

RGB numbers are usually measured on a scale of 0-255, unless you are working in Lightroom. In Lightroom, you generally see them on a percent scale. 0% is the darkest value for any color, it’s so dark that there is no visible detail in that area. 100% is the brightest, and is so bright that no detail is visible.

Analyzing the color numbers

When analyzing RGB numbers for skin tone, look for the following indicators:

- Red should be higher than Green. Green should be higher than Blue. This pattern is universal to all skin tones, regardless of age or ethnicity.

- Each color should have at least a 2% difference, usually more, between it and the next number. Do you know how to identify a pure gray? That is a pixel that measures exactly the same in its Red, Green and Blue numbers. So skin whose RGB numbers are very close to each other is going to look gray. Not very appealing, right?

- If any colors measure 94% or above, you probably have overexposure to deal with.

- If any colors measure 6% or below, you probably have underexposure to deal with.

The RGB numbers in the photo above are consistent with expectations. This means that the skin is within “proper range” of a well-exposed photo with good white balance.

What do to with bad numbers?

What happens, however, if your photo doesn’t look so good straight out of camera?

In this photo, the measurement point was just next to the arrow on her forehead. The numbers read: Red 93.8%, Green 92.5%, and Blue: 93.6%.

Anytime you see a photo with skin tones that measure like this, your eyes are going to tell you that something is off before the numbers do. The benefit of using the numbers is that they give you the direction to which your edits for the image need to go.

The numbers in this photo cause concern because:

- Anything higher than 94% or so in Lightroom is bright enough that your image, if you print it, might not render good detail in those areas. That means that these areas are too bright.

- Blue is higher than Green. Red should always be the highest and Blue the lowest otherwise the skin tone will appear cold.

- The RGB numbers are too close together – they are approaching gray. This skin in this photo is lifeless as a result.

Correcting the skin tones

To fix this image, you would start by tweaking exposure. Proper exposure is a huge component of proper skin color. In fact, it’s often impossible to assess skin tone issues correctly without correcting exposure first.

A little-known bit of Lightroom awesomeness is that it’s easy to correct exposure while keeping an eye on the RGB numbers. In the Develop module, double click in the numeric entry field for Exposure so that the number is highlighted. Next, hover your cursor over the area of skin you are measuring without clicking. Use the up or down arrows on your keyboard to change exposure until a more appropriate measurement for the Red value appears under the histogram.

Adjust Highlights (or Shadows, Whites, or Blacks) in the same way. Activate the numeric input field for editing then hover the cursor over the arrow you want to measure. Use the arrow keys on your keyboard to increase or decrease the adjustment.

Exposure for this photo is better with the adjustments you see above, but color is still off. When the RGB numbers are as close together as you see here, it’s often better to use Color Curves than the White Balance sliders to fix the issue.

Using Color Curves instead of White Balance Sliders

Color Curves has two major advantages over the white balance (WB) sliders.

You might have noticed already that Lightroom measures three colors (red, green and blue) for each pixel. However, the White Balance sliders don’t allow for editing the most important component of skin color – red. But, you can edit Red tones using Lightroom’s Color Curves.

The other big benefit of using Color Curves is that you can adjust colors in limited parts of the tonal range. For instance, if you reduce yellow in an image using the Temperature slider in the White Balance section, you are reducing yellow globally (everywhere in the image equally). Using Color Curves, however, you could reduce yellow only in the shadows, without taking away the yellow that properly belongs in the mid tones and highlights of an image.

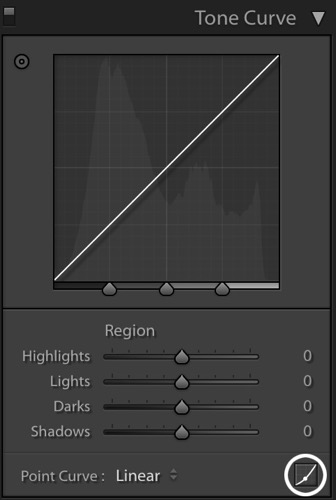

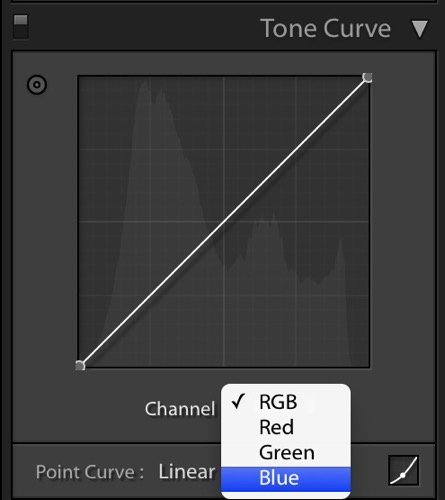

To find Color Curves in Lightroom, scroll down to the Tone Curve section. By default, it shows you the parametric curve, which looks like this:

Click on the small button in the lower right corner of the Curves panel to access the Point Curve. (It’s circled in the screen shot above.)

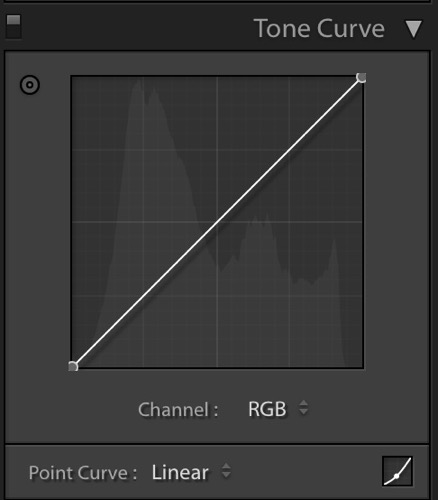

Now you are looking at the Point Curve interface:

Using the Channel drop down menu, select the color you’d like to adjust.

Which color channel to edit?

At this point, you may be wondering about adjusting colors other than red, green, and blue. For instance, what if your photo has too much yellow or orange? Think about it like this.

Each of the three colors measured in Lightroom has an opposite:

- Red is the opposite of cyan

- Green is the opposite of magenta

- Blue is the opposite of yellow

Reducing any one of those colors using Color Curves, increases that color’s opposite. In other words, reducing blue is the same as increasing yellow.

Looking at the Curves panel, do you see the histogram behind the straight line? When you click and drag the straight line to create a curve, this tells Lightroom to adjust the pixels corresponding to that part of the histogram.

Say, for instance, that you wanted to add blue to the mid tones of an image. You would select the Blue channel and click the line in the middle of the histogram, where the midtones live. Dragging the line up would add blue to the bright parts of your photo’s tonal range.

Dragging up increases the color the channel is named after – blue, in this case. If it increases blue, that means that it’s also decreasing blue’s opposite, yellow.

Dragging down decreases the color the channel is named after.

Using the Targeted Adjustment Tool for Curves

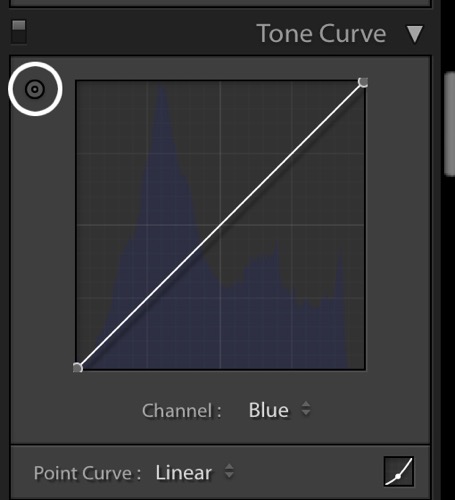

That’s the way it works in general. But you can get much more precise color control by using Lightroom’s Targeted Adjustment Tool. Click on the button at the top left corner of your Curves panel to activate it (circled below).

Hover this tool over the spot you’re using to measure the skin tone in your photo, but don’t click! Use the up and down arrows on your keyboard while keeping an eye on the RGB numbers beneath your histogram until the both the appearance of the photo and the RGB numbers improve.

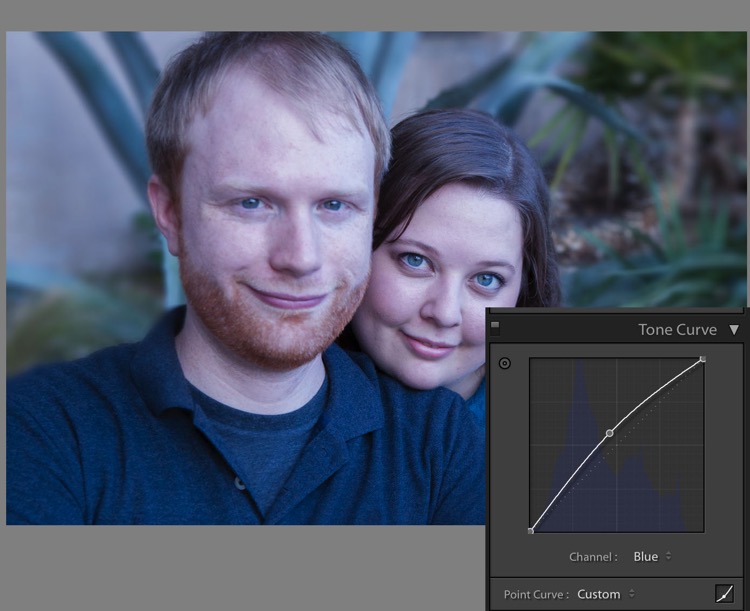

Moving the blue curve down, as in the screenshot below, provides better separation between the Green and Blue measurements. It also gives the photo the warmth it’s lacking.

If the image still lacks vibrance, as this one does, move to the Red curve and increase the Red channel. Adding a touch of red is the best way to counteract gray skin.

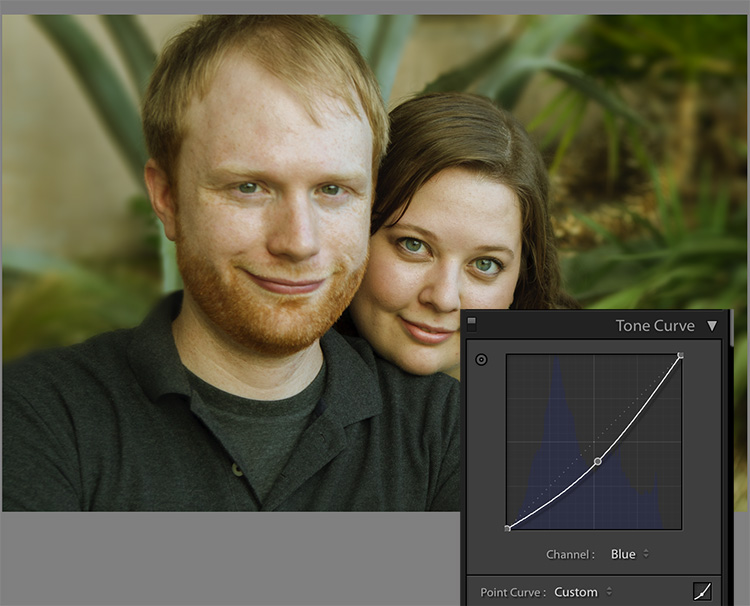

Next, decreasing green (to add magenta) makes the skin color, as well as the corresponding RGB numbers, look just about right.

Tweaking things

However, the warmth of the plants behind them is overpowering the subjects. To downplay it, return to the Blue channel.

Using the Targeted Adjustment Tool, add Blue to the the shadows by hovering over a dark area of the photo and hitting the up arrow on your keyboard.

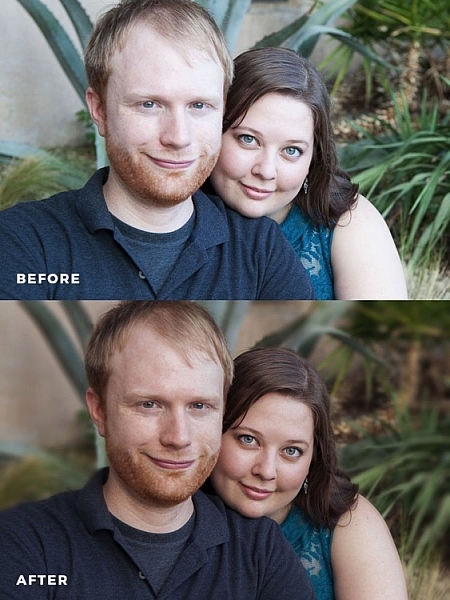

Compare the original and edited photos here:

Before

After

Editing your own images with Color Curves and RGB numbers

Keep the following tips in mind when editing your own images.

#1 – First, a big caveat to anyone who has heard that using RGB numbers to edit will solve all skin tone problems! There are as many proper RGB measurements as there are people in the world. As you study RGB numbers, let trends in the numbers and generalities guide your edits, but don’t try for an exact numeric match.

#2 – Measure skin tones in the middle range of brightness. Look for mid-tones rather than bright highlights or deep shadows. Also avoid measuring on cheeks, the end of the nose, or other areas that are usually redder than others.

#3 – In general, when I’m editing photos, I look for tones in these ranges:

- Red is highest > Green is middle > Blue is lowest – always.

- The Red channel is usually between 70% and 90%. Very light skin can be as high as 94%. Very dark skin can go as low as 40-50%.

- The Blue channel is usually between 30% and 80%.

- It’s not possible to generalize how many percentage points difference should be between Red and Green, or Green and Blue. However, skin that has warmer tones will have less Blue in proportion to Red and Green.

#4 – Small movements of your tone curve impact your image dramatically. Don’t go overboard!

Conclusion

Studying the patterns in the RGB numbers of your photos is a great way to develop your editing eye. Everyone has photos that aren’t quite right. Analyzing the relationship between the numbers and the appearance of the photo will help you get to the point where you can eyeball a photo’s needs without referring to the RGB numbers at all.

Any questions? We could talk about this topic all day. Comment below and tell me what you think.

The post How to Correct Skin Tones Using Lightroom’s Color Curves by Erin Peloquin appeared first on Digital Photography School.